|

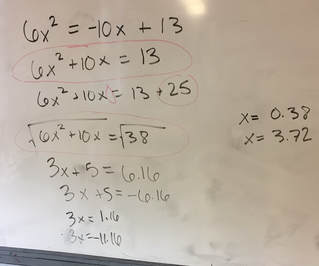

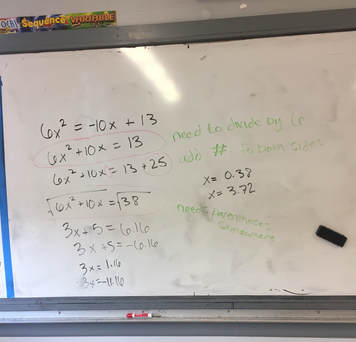

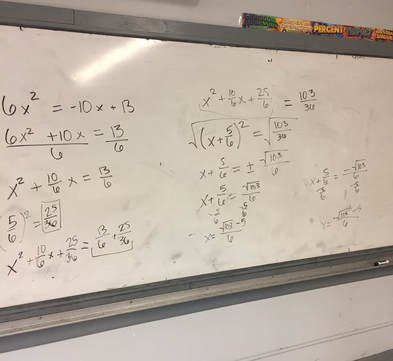

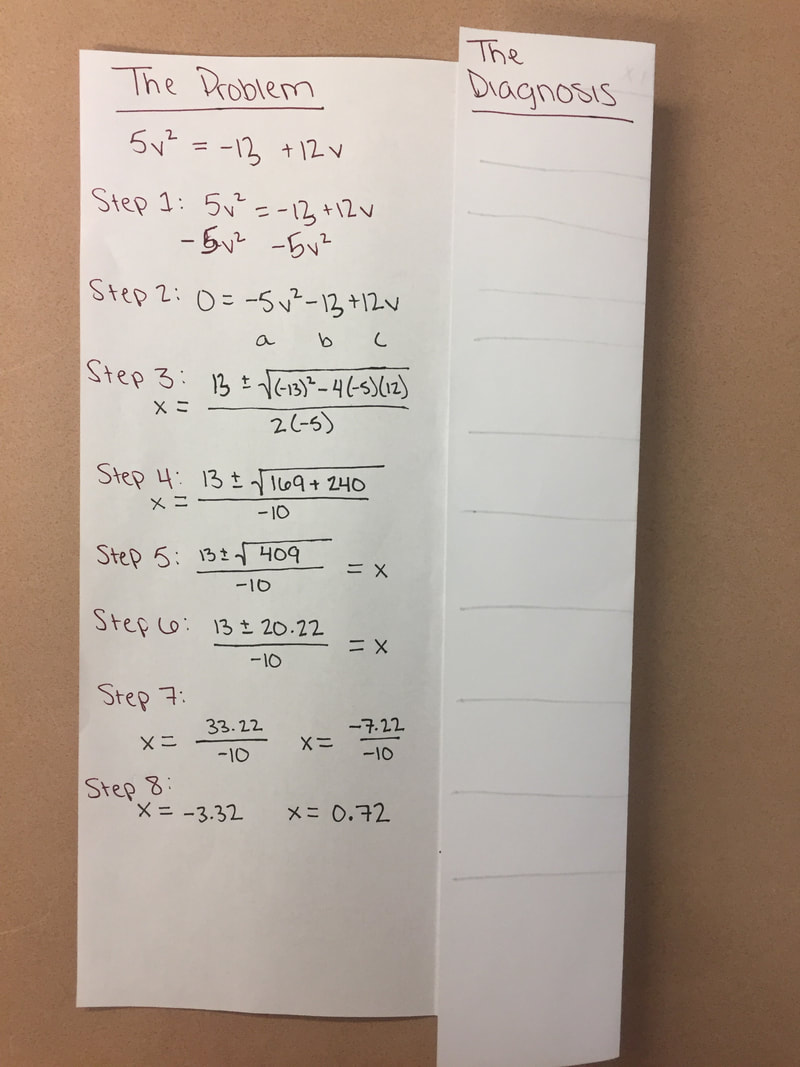

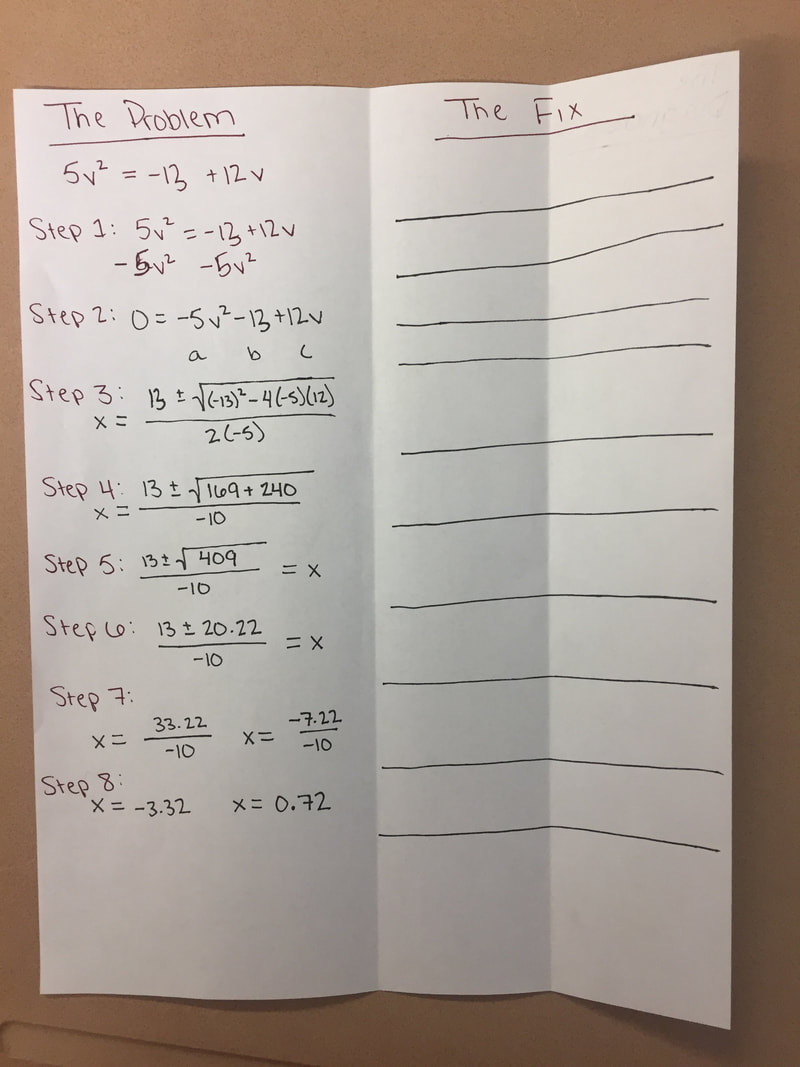

There's one very important thing you should know about me as a teacher. I am a very big fan of all things dorky, dweeby, or lame.This self-proclaimed dweebiness has taken a lot of forms in my classroom over the course of this year. I've sung songs, worn silly headbands, handed out valentines, created fake dating profiles for functions, the list goes on. Today, my dweebiness took the form of a new activity I called, "Math Hospital." Borrowed from this post I saw on The Art of Education, the Art Hospital easily transformed into a Math Hospital. Essentially, the idea is that students are given a piece of art with a "mistake" on it (an ink blob, a weirdly-placed piece of tape, etc.) and their task is to turn the art back into a masterpiece by working with the mistake. I am currently working a lot with my Honors class trying to get them to accept that mistakes are an inevitability, they do not make you stupid, and they are something that can be corrected and that will help us learn. Let it be known that the original activity is not dorky, dweeby, or lame. I created my own dweebiness by adding some silly group roles and insisting on calling all of my students "doctor" for the entirety of the class period. Here's how I adapted the Art Hospital to become the Math Hospital: 1. The PatientWhile the students were doing their warm-up, I put a problem on the board and wrote out all the steps taken to solve it. I borrowed mine from some student work we didn't get around to discussing the day before, but you could easily select a problem and solve it through yourself with a few intentional errors. I liked using real, anonymous student work because the mistakes were organic and the student whose work it was got some valuable peer feedback without feeling called out. 2. The Nurses

3. The Doctors

4. The Surgeons

Group-Worthy PracticeAfter modeling the procedure as a class, students were assigned roles as either a Nurse, Doctor, Surgeon, or Medical Scribe (our Math Hospital version of recorder/reporters) and given their own "patients" to work on. The "patients' charts" were structured with the problem on the left, and a folded column for the nurse to make some initial notes on the right. That unfolded into an area for the doctor to write down a plan of action right beside the original problem. The surgeon worked through the problem on the back of the sheet. Once they got through with one patient, the roles would rotate Student ResponseThe kids got way more into the activity and the roles than I thought they would! They really embraced the act - "Hold on Ms Johnson, we're getting out our scalpels", "He's losing blood! Speed it up!" "I think ours is dead on the table" could be heard the whole time. This is a class that had also struggled to embrace group roles in the past, and assigning titles like doctor or nurse really helped them be mindful of their jobs.

From a teaching perspective, I liked this activity for a couple of reasons. It gave me an authentic chance to use the group roles, which was great. It also put an emphasis on healing from errors - everybody's patient got out alive. This was really needed with my group of kids, since they still see making a mistake as being a sign of being stupid. The last reason I really liked it was that the roles gave me an opportunity to assign competence and give power to some new groups of students. My typical table of boys who always shout out the answers ended up being my medical scribes, a group that was usually quiet and didn't get a lot of classroom "glory" were doctors, and some of my students with the biggest fear-of-failure issues took on the surgeon roles to get practice fixing mistakes once they've found them. It wound up giving the room a nice mix of voices that don't usually get heard, and some good practice in skills that are going to help us grow out of that fear of mistakes.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAs an educator, Abigail Johnson reflects on several relevant topics impacting today's students in mainstream classroom settings. Archives

March 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed